Seared Dandelion Hearts

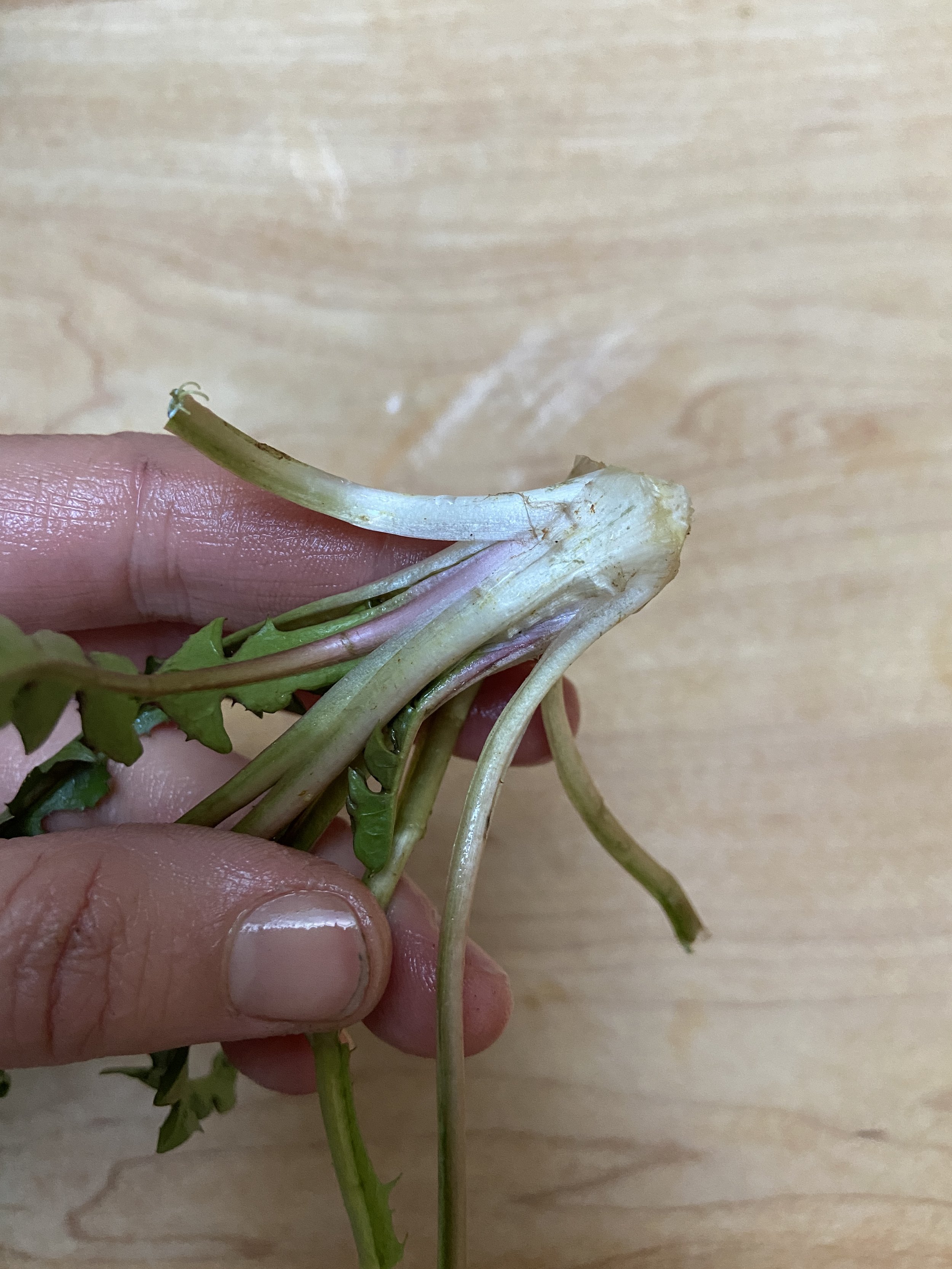

Dandelion hearts (aka dandelion crowns) are even more under-appreciated than dandelion greens, but they are really incredible - kind of like eating an artichoke heart vs. the artichoke leaves. They have the best texture and more mild/less bitter flavor when harvested in the early spring/late winter (or from young plants). It does take a bit of digging to unearth them, but they’re worth it! Because they have similar properties as something like chicory or raddichio, I think they are most delicious seared or wilted with a salty umami dressing with citrus zest. This recipe calls for anchovy, but it can easily be substituted with miso. Would pair beautifully atop polenta or in pasta/ramen noodles!

To harvest: Dig out the dandelion so that you remove the entire base or “heart”. You can also dig up the roots at this point if you want to use them or if you’re in a situation where you’re also weeding a garden and don’t want the dandelion to grow back. Unlike some other foraged wild ingredients, dandelion doesn’t not need to be rationed:) I keep meaning to make dandelion bitters, so maybe I finally will(?)

Ingredients:

6-8 dandelion hearts + tops (you can save the tops for something else if you want)

3 anchovies or 1 tablespoon miso

Juice from 1 lemon or 1-2 tablespoons red wine vinegar

2-3 tablespoons olive oil, separated

Citrus zest - I used orange this time

Black pepper (optional)

Clean dandelion hearts well - I soaked in water a few times and checked between the crevices to make sure dirt was removed.

Chop anchovies and mix with lemon juice using a fork until it creates a paste (a few chunks of anchovy is a-okay). I like to do this in a jar so I can shake it with the olive oil.

Add 1 tablespoon olive oil, mix/shake in jar, and set aside.

Drizzle olive oil in pan (I like to use cast iron for browning) on medium-high. Once hot, add dandelion crowns. Toss for a few minutes, tossing occasionally, until softened and slightly browned. Toward the end, add the dandelion greens and dressing (shake dressing first if it has separated). Toss and remove from heat onto plate.

Top with Citrus zest and black pepper. Add another drizzle of olive oil if needed.

Voila.

Spiced elderberry cordial

Unlike elderflower cordial, elderberry cordial is a stronger, thicker syrup containing alcohol that is used in both medicinal and culinary applications. The syrup is sometimes taken regularly for cold and flu prevention (there is limited peer-reviewed, but much anecdotal evidence suggesting the berries enhance immune response), to top pancakes, or, as I particularly enjoy, with champagne for an “elderberry kir royale”. Feel free to experiment with the spice blend, add other ingredients such as citrus peel and herbs, or keep it simple with just the berries.

1 1/4 cups dried elderberries or 2 cups fresh

1 cinnamon stick, crushed

1 star anise

About 3 cups brandy

Honey, to taste (maple syrup or other sweetener can be substituted for honey)

Place elderberries, cinnamon, and star anise into a clean quart-sized glass jar. Add brandy to fill the jar and cover with a lid. Label the jar with contents and the date. Set aside in a cool, dark place for 3 to 4 weeks.

Strain cordial through cheesecloth over a large bowl. Squeeze contents of cheesecloth to release remaining liquid into the bowl then discard solids.

Add about 1/2 cup sweetener, such as honey, for every 1 cup liquid (or to taste). Stir to dissolve. Using a funnel, pour cordial into a clean bottle (or several clean bottles) and seal with cap or cork. A cordial using fresh

A cordial made with fresh elderberries will last about a year, whereas a cordial made with dried berries will last for 2-3 years and improve with age. Store in a cool, dark place and use as a cold and flu preventative, over desserts, or in beverages.

Plantago, Butter, & Thyme Morsels

Plantago seedpods are as great for eating as they are for flinging!

Plantain (Plantago major and Plantago lanceolata) is easy to recognize and grows everywhere. You probably have some growing within a block of where you are RIGHT. NOW. Plantago major is the plantain with the wider, oval-shaped leaves and Plantago lanceolata is the plantain with the thinner leaves (lance-shaped, as the name indicates). I will save explanation of of the plantain in general and using the leaves for another post (in short: the leaves can be eaten as you would other greens, ideally cooked, as they are quite fibrous) and focus this post on the late-spring/summer/early fall delicacy - plantain seed pods.

When I was young we used to catapult the brown seedpods by wrapping the stem around the pod and flinging it. This is an enjoyable activity to this day, BUT maybe instead of flinging the pods at your sister (ahem - you know who you are!), fling them into a pan with some butter and thyme to prepare this simple, delicious recipe. Alternatively, just cut or pull off the pod stems away from the plant.

Entire Plantago lanceolata, complete with leaves, seedpods and roots.

When I first heard that these seedpods tasted like morel mushrooms I didn't think it was possible, but I was wrong - it is. I promise - give it a try and you will see. The other great thing about these pods is that they are packed with psyllium, a form of fiber that is often added to foods to increase dietary fiber content, as well as calcium. Yes, that's right - grow everywhere, taste like morel mushrooms AND high in nutrients. The pods can also be broken up into smaller seeds and toasted in a pan with herbs and spices to sprinkle on top of salads/popcorn/etc. or eat as a snack. This method of preparing plantago seeds is very simple, so there is no excuse not to try!

To Prepare:

Heat butter and/or olive oil (enough to coat bottom of pan) in a cast-iron pan on medium-high.

Add seedpods (with or without stems, I like to include the stems to use for serving) and heat for 2 minutes, tossing to coat in butter/oil. Add thyme and a sprinkle of salt and continue cooking another 1-2 minutes, stirring occasionally until pods are toasted and seeds just begin to fall off. If seedpods look to dry, add more butter or oil and toss to coat.

Serve immediately. If stems are still attached, they can be used as a serving stick (eat just the pod off of the stem - the stem is very tough).

Sautéing seedpods in cast-iron. At this point, they have soaked up all of the butter/oil and if I need to cook them longer I would have to add more.

Pickled Magnolia Blossoms

Pickled magnolia blossoms

Fresh and pickled magnolia blossoms.

When magnolia trees bloom, they aren’t shy about it - they burst forth in seductive, fragrant glory and leave a slew of thick, oxidizing, hard-to-clean-up flowers in their wake. I love them for this and was pleasantly surprised to find out that the blossoms are also edible. Let’s be honest, these past two (pandemic) springs has been surreal and anxiety-provoking, so having an excuse to go outside and work on a foraging project is and was definitely appreciated. Most magnolias bloom in the spring and all varieties of Magnolias are edible - star magnolia, saucer magnolia, lily magnolia - you name it. The blossoms have variations in color/flavor/texture, so I’d recommend tasting a sliver and seeing what works best for you. Fresh, they have a texture similar to endive with a spicy/floral flavor.

Uses: Prior to this experiment, I’d only used fresh magnolia petals to top desserts, more for decorative purposes than anything. But, you can also use them in small amounts in salads/grain bowls/etc. or they can be pickled, which is the most common application. I would like to try infusing a liquor with them as well, but haven’t gotten around to that yet! Any time you handle the flowers (if you care at all about their appearance) it’s important to be very careful, as the petals bruise/brown easily.

Gorgeous magnolia blossom - for eating raw, the younger leaves are best.

Pickled Magnolia Blossoms: This recipe is an adaptation/combination of two recipes I found (shoutout Medium and eatweeds.co.uk) along with what seemed like it would work and taste the best to me. You can liken the final product to a strong/very floral pickled ginger (with an appearance/texture to match). As you might guess, they work really great with Japanese/Asian flavors like sesame, soy, and seaweed - I’ve used them in a miso noodle bowl (pictured below) and am looking forward to trying it out in a brown rice/sesame bowl or maybe with some homemade sushi/salmon? I could see pickled magnolia being great in any application where pickled ginger sounds good, but also creamy foods to counter the spicy like a compound butter or mild fresh cheeses. The vinegar can be used as you would use regular vinegar as well - for both petals and vinegar, a little goes a long way. Below recipe makes about 1 cup.

220g magnolia flowers (about 6-7 cups packed) - For pickling, it’s ok to have older leaves. For eating fresh you want the younger nicer leaves.

500mL rice vinegar (about 2-¼ cups) - Other light-bodied vinegars or a combination also works, I see a lot of people use apple cider vinegar, but I wanted the subtlety of the rice vinegar.

110g granulated sugar (about ½ cup)

2 teaspoons Kosher salt

To Prepare

Clean and dry flowers - carefully so you don’t bruise the petals.

Add petals to a quart jar or two pint jars (pack tightly). Naturally, jars should be clean.

Heat vinegar with sugar and salt to simmer and sugar/salt is dissolved, stirring as needing.

Pour hot brine over petals.

Using a clean spoon or other utensil, submerge petals under brine several times as they inevitably rise to the top. Optional: I like to use a clean plastic bag or smaller mason jar with a little water to make sure the petals stay submerged.

Cover with lid, allow to come to room temperature, then refrigerate.

Pickled blossoms are ready in 24 hours and will keep in the refrigerator for 4 months to 1 year (still looking into this as I keep them in my fridge - I know that the color will become browner).

Pickled magnolia blossoms in a bowl of miso-ramen.

Prickly pear salty caramels

Prickly pear margaritas, prickly pear sorbet, prickly pear cheesecake, prickly pear fermented beverage, prickly pear marinade - you name it, I've tried it with prickly pear. This is primarily because at my house in Oakland has a giant prickly pear cactus (Opuntia) that is very, VERY productive. Like, part-time job in the late summer/fall productive. At first, I was so pumped that I wasn't very generous with the fruit, but now, when I hear someone comment on the prickly pear cactus (which happens quite often) I run out and give them a bag of frozen fruit. You can read more about my harvesting methods here. Since there's so much fruit, I now pretty much stick to the second process listed, which is a loss of the pulp, but dramatically less work.

Cutting caramels into squares.

A few years ago, in an effort to get rid of as much juice as possible, I was trying to think of recipes where reducing the juice was required. I remembered making apple cider caramels at some point, so I decided to give that a try using this Smitten Kitchen recipe for apple cider caramels, but substituting out cider for prickly pear juice. There are also a few other changes, like adding cacao nibs to the top and omitting cinnamon (wouldn't be bad, but just already a lot going on). The caramels were above and beyond my expectations - a deep, rich sweetness balanced by the salt and toasty cacao nibs. Really so, so good and now my favorite prickly pear concoction. Additionally, they can be wrapped and keep well, so a great unique holiday gift item! Recipe makes about 50 caramels, depending how large they are cut.

4 cups (945 ml) prickly pear juice

8 tablespoons (115 grams or 1 stick) unsalted butter, cut into chunks

1 cup (200 grams) granulated sugar

1/2 cup (110 grams) packed light brown sugar

1/3 cup (80 ml) heavy cream

Up to 1/4 cup cacao nibs

Up to 2 teaspoons flaky sea salt, such as Maldon, or less of a finer salt

Neutral oil for the knife, if needed

Boil the prickly pear juice in a 3- to- 4- quart saucepan over high heat until it is reduced to a dark, thick syrup, about 1/2-3/4 cup in volume. This takes about 40-60 minutes on my stove. Stir occasionally.

Meanwhile, get your other ingredients in order, because you won’t have time to spare once the candy is cooking. Line the bottom and sides of an 8- inch square metal baking pan with 2 long sheets of crisscrossed parchment. Set it aside. Put salt and cacao nibs in a small dish.

Once you are finished reducing the juice, remove it from the heat and stir in the butter, sugars, and heavy cream. Return the pot to medium- high heat with a candy thermometer attached to the side, and let it boil until the thermometer reads 252 degrees, only about 5 minutes. Keep a close eye on it. Stir occasionally. (Don’t have a candy or deep- fry thermometer? Have a bowl of very cold water ready, and cook the caramel until a tiny spoonful dropped into the water becomes firm, chewy, and able to be plied into a ball.)

Immediately remove caramel from heat and give the caramel several stirs to distribute it evenly. Pour caramel into the prepared pan then sprinkle with cacao and salt. Let it sit until cool and firm—about 2 hours, though it goes faster in the fridge. Once caramel is firm, use your parchment paper sling to transfer the block to a cutting board. Use a well- oiled knife, oiling it after each cut (I have never had to do this...), to cut the caramel into 1-by-1-inch squares or 0.5-by-2-inch. Wrap each one in a larger piece of parchment or wax paper, twisting the sides to close. Caramels will be somewhat on the soft side and will keep for 2 weeks at room temperature, 1 month in the refrigerator.

Gnocchi with porcini and Wilted wild greens

Gnocchi - the pasta of potatoes. If you see gnocchi as simply a vehicle for toppings then you haven't tried legit gnocchi. Making gnocchi from scratch may take time and attention, but the effort is worth it. The resultant soft, pillowy dumplings are stars of the show as much as any sauce. The first time I had the pleasure of tasting homemade gnocchi was in Turin, Italy when I was there for the Slow Food Terra Madre conference and I can still remember the meal - it was that good. My gnocchi may not quite achieve the same level of perfection, but I'll certainly keep trying.

I've made gnocchi several times in the past, each time with a different topping, and I really like how the richness of the mushroom sauce and the green notes of the wild greens (in this case, curly dock - more on the plant in general here) paired with the simple potato pasta in this recipe. The next time I make it however, I will blend the mushroom sauce with an immersion blender for a smoother consistency that doesn't compete with the soft gnocchi "pillows". Feel free to take just the gnocchi portion of this recipe and experiment with your own combinations, such as different mushrooms, a pesto, or a simple marinara sauce. Recipe serves 4.

Gnocchi

Wee little gnocchi dumplings.

2 pounds of golden potatoes

1/4 cup egg, lightly beaten

1 cup all-purpose flour

Sea salt (fine grain)

Fill a large pot with water. Salt the water, then cut potatoes in half and place them in the pot. Bring the water to a boil and cook the potatoes until tender, about 25-30 minutes.

Working one potato at a time, remove potato halves with a slotted spoon and place on a large cutting board. As soon as possible after removing from the water, peel each potato before moving onto the next (these are, obviously, hot potatoes, but you want to work as fast as possible to mash them while they're still hot). Mash potatoes using a fork to create a mound of potato "fluff" - do not over mash. Save the potato water for later.

Let the potato mash cool for about 5 minutes (you want to prevent the egg from cooking). Join the potatoes into a soft mound, drizzle with the beaten egg and sprinkle 3/4 cup of the flour across the top. Using a spatula, scrape underneath and fold to mix in egg and flour. With a very gentle touch, knead the dough. Knead in more flour if dough is too gummy/tacky. The dough should be moist but not sticky.

Lightly flour a new cutting board and separate potato dough into 8 pieces. Gently roll each 1/8th of dough into a log, roughly the thickness of your thumb. Use a knife to cut pieces every 3/4-inch. Dust with a bit more flour.

Shape gnocchi using a fork to create lines in the middle of the gnocchi, so that they kind of look like footballs. Be sure to lightly touch fork into the gnocchi so that it still stays soft and doesn't break. Set gnocchi aside, dusting with flour if needed until you are ready to boil them. Meanwhile, make the porcini sauce.

Porcini Sauce

1.5 cups low-sodium chicken broth

0.75 ounces dried porcini mushrooms, rinsed

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 small shallot, minced

1 clove garlic, thinly sliced

1/3 cup dry white wine

2 tablespoons minced fresh parsley

Salt and pepper

Heat broth and porcini in a small saucepan until simmering. Turn off heat, cover, and Let stand until softened, about 5 minutes. Remove mushrooms, reserve liquid, and dice porcini. Heat 1 tablespoon olive oil in a medium skillet over medium heat. Add chopped porcini, shallot, and garlic; cook until lightly browned, 2 to 4 minutes. Stir in reserved liquid, wine, and remaining tablespoon olive oil, scraping up any browned bits. Increase heat to high and bring to boil; cook to reduce, whisking occasionally, about 5 minutes. Stir in parsley and season with salt and pepper to taste. Cover to keep warm.

Cooking and Serving Gnocchi

A few handfuls of foraged dock, dandelion, or other green, thoroughly washed and trimmed

Olive oil drizzle, salt, and pepper, for garnish

Parmesan shavings, for garnish

Reheat the potato water and bring to a boil, adding more water if needed (you need enough water to cover the gnocchi). Cook the gnocchi in small batches by dropping them into the boiling water. Once gnocchi pop up to the top, remove them with slotted spoon ten seconds or so after they've surfaced. Have a large platter ready with dock or other greens that you will be serving with the gnocchi on the plate. Place the gnocchi on the platter on top of the greens - greens will wilt from the heat of the gnocchi. Continue cooking in batches until all the gnocchi are done. Top gnocchi with porcini sauce, a drizzle of olive oil, salt, black pepper, and parmesan shavings.

California Capers

California Capers.

As I explore in a previous post, the nasturtium plant (Tropaeolum majus) has so much more going on than a pervasive vine with peppery bright flowers, including incredibly spicy leaves and (the subject of this post) pungent, clear-your-nasal-cavity seed pods. You want to pick the seed pods when they're young and green, as they toughen and get bitter with age (but are still edible). Try them raw - their wasabi-like flavor is so intense, it'll wake you right up! I like eating them as a snack, but as they are so intense a little goes a long way. By pickling them, you can preserve and enjoy these pearls of flavor for up to one year. As with most things in the culinary world, someone else has already done this and coined them "California Capers" - a designation I love and truly wish I'd created!

The nasturtium plant in all its glory.

Nasturtium seed pods stuck together in groups of three - these need to be separated before washing and preserving.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.

I've tried making California capers a few ways, some ways more complex than others, but I find that I like the simple version from this site best, with a few alterations. If you find the caper pungency to be too strong, you can always submerge them in a salty brine for a few days (1/4 cup salt: 2 cups water). Pickled nasturtium pods work anywhere you'd use regular capers - they're amazing on bagels and lox (anything with smoked or preserved fish, really), pasta pomodoro, braised chicken, in tuna or egg salad, green salad, etc.

Makes 1 pint

1-1/3 cups young nasturtium seed pods

2 bay leaves

About 1-1/3 cups distilled white vinegar

2 teaspoons Kosher or sea salt

Separate seed pods that are stuck together - they are often joined in groups of three.

Soak seed pods in water to remove any dirt/debris, then drain and place in two sterilized half-pint jars along with 1 bay leaf per jar.

In a small saucepan over medium-high heat, bring the vinegar and salt to a simmer and stir until salt is dissolved. Pour hot vinegar mixture over seed pods, covering them completely.

Let the jars cool to room temperature before sealing with lids. Refrigerate for at least 24 hours before eating and enjoy for up to one year.

Rumex Crisps: Dock Seed Crackers

The latin name for curly dock, a wild plant with edible leaves and seeds, is Rumex crispus (see previous post for foraging/harvesting info). Thus, when I decided to use the toasted seeds in a cracker, the name was obvious. Let's be honest - I made these crackers specifically because I came up with the name Rumex crisps. I'm a sucker for wordplay. On the plus side, the seeds paired beautifully with the rye flour for a delicious, crispy, nutty-tart cracker that is great alongside rich creamy cheeses and sweet dried apricots (or other fruit). The below recipe makes about 36 2-inch crackers, depending on how thinly you roll out the dough.

Toasted vs. raw dock seeds.

1/2 cup toasted dock seeds

3/4 - 1 cup rye flour

1/4 teaspoon sea salt, plus more for sprinkling

1 tablespoon grapeseed oil, plus more for brushing

1/2 tablespoon honey

1/3 cup water

Preheat oven to 300 degrees F.

In a large bowl, blend together dock seeds, 3/4 cup rye flour, and salt. Stir in grapeseed oil, honey, and water until incorporated. Add more rye flour as needed so dough is no longer sticky, but still moist.

Divide dough in half and roll out thinly on a floured surface (not paper-thin, but "cracker-thin"). Don't stress too much about the thickness - if the crackers are thicker, they'll just take a bit longer to cook.

Cut crackers into any shape that you like, such as squares, diamonds, or strips, and place them on a baking sheet. Crackers can be close together, as they hold their shape as they cook. Gather dough scraps, re-roll, and cut as needed. Repeat with remaining dough half.

Brush crackers lightly with grapeseed oil (or rub with fingers), sprinkle with a little more salt, and bake for 15 - 20 minutes. Remove from oven and cool on rack. Store in an airtight container and enjoy for up to 2 weeks. If you live in a humid environment, crackers can be re-toasted in the oven.

A diamond-shaped Rumex crisp with a creamy sheepsmilk cheese and vetch tip flower.

Umeboshi with Wild Plums

Umeboshi wish California wild plums.

Wild plums and red shiso make for impressive color.

As it turns out, you can't find ume plums (Prunus mume) easily on the West Coast to make a truly traditional umeboshi, or Japanese salt-pickled plum. Fortunately, wild plums are small and tart enough to work in much the same way. Ume plums are actually more closely related to an apricot, so if you eat them raw the texture will (theoretically, I have never eaten them myself) be very different than a wild plum from the West Coast, but when pickled the different is very subtle.

By preserving wild plums in salt, you keep the harmful bacteria out and, over time, create many amazing complicated flavors. The resulting wild plum umeboshi can be chopped and used as a condiment to bring bright, tart, pungent, savory/sweet flavor to a wide variety of dishes. Traditionally, it's eaten with rice, but I've tried it sautéed with sweet corn and in a nectarine compote that topped seared pork and I'm definitely looking forward to more experimentation! The salty-tart juice leftover from the umeboshi can be used for quick-pickling radishes or as an interesting addition to sauces and dressings.

One of my favorite discoveries - sautéed sweet corn with umeboshi and butter.

The below recipe is adapted from from here, which is supposedly the most popular umeboshi recipe translated into English and can be adjusted as needed for amount of plums that you have. We made a few batches with shiso (purple shiso from our garden) and a few without and although the shiso is nice, it's pretty subtle and both versions are great. Be careful handle the plums VERY gently - any bruising and cutting can lead to mold.

1 pound (metric example = 1 kilogram) small wild plums, about the size of cherries or slightly larger and still firm (we picked up red ones from Tilden Park - yellow can be used, but the color will not be as characteristic)

2 cups (metric example = 1 liter) vodka or other distilled alcohol (such as shochu), for rinsing plums

1.6 ounces (metric example = 100 grams) red shiso leaves (about 10% by weight of plums)

1.6 ounces (metric example = 100 grams) coarse sea salt or Kosher salt (10% salt solution)*

Step 1: Sterilized the plums and process the shiso

Remove stems from plums. Wash plums in water twice then soak in a bowl of cold water and allow to soak overnight. This removes some of the bitterness in the plums (wild plums are less bitter than ume plums, but I went ahead and did this to be safe).

Drain plums, dunk in a bowl of vodka, and set out on a clean towel to dry. The alcohol helps to ensure any mold spores that might still be on the outside of the plum are removed/rendered safe.

Wash shiso leaves, remove tough stems, sprinkle with salt and massage leaves with fingers until they are limp.

Step 2: Get your plums nice and salty so they ferment

Clean a large, wide-mouthed container (such as a gallon-sized jar) that can hold all of your plums. Spray with vodka to disinfect it, then allow to air dry.

Fill your pickling container with salt and plums by starting with a layer of salt, then a layer of plums, followed by a portion of shiso. Repeat until all ingredients are used and weigh down with a plastic bag filled with water or another smaller jar filled with rocks and water (make sure these are clean). Once the container is full and weighed down, cover the top with cheesecloth and secure with a rubber band. You might have to wrap cheesecloth around the weight then secure with a rubber band. As long as the top is covered with cheesecloth, all is well. It doesn't have to be pretty!

Salt, shiso, and plums weighted down and covered with cheesecloth.

Leave fermenting plums in a cool, dark area until the plums are soft and completely immersed in a reddish liquid (about 1-2 weeks). This liquid is extracted from the plums by the salt. If liquid is not completely covering plums, try increasing the weight. Liquid should be about 1 inch above the top of the plums. Leave the plums in the liquid until you are ready to dry them, about 2-3 weeks.

Step 3: Hoshi/boshi ("to dry") your plums

Wild plums (or ume plums in Japan) are harvested in June and drying traditionally occurs on a specific date after the rainy season is over. Be sure to dry your plums at a time when the weather is dry and at least 2 weeks after plums have been submerged in liquid.

Put the plums in a single layer and the shiso leaves in spread-out clumps separately on flat baskets - we used a bamboo steamer - . Leave the baskets outside in a sunny place with good ventilation for about 3 days, turning them at least every 24 hours. If it rains, be sure to take them inside before they get wet. At the end of the drying process, they should look wrinkly.

Umeboshi drying on bamboo steamer liners. Also in the photo are green walnuts in the process of pickling (but have nothing to do with the umeboshi, don't be confused!)

Step 4: Store and enjoy

Store plums in jars, pouring back in some of the ume liquid if you prefer softer plums (we did not do this, as we like them firmer). As I mentioned earlier, this ume liquid can be used for other things, such as quick pickles. The shiso leaves can be layered in with the plums, but we keep the shiso out for other uses, as they didn't have the best texture and we wanted to keep our umeboshi "clean". The umeboshi is now ready to eat - they can be eaten for up to 10 years (!) and grow in complexity over time, but I doubt we'll still have ours after even 1 year!

*Other salt solutions can be used, from 8% - 20%. The higher the salt percentage, the saltier the umeboshi will be (obviously). The lower the salt percentage, the more likely they are to mold. It is recommended that beginners use at least 10%.

Finished umeboshi straight from the jar.

Elderflower Chive Fritters

A savory twist on a wild spring treat.

Chives provide brightness without overpowering the elderflower.

As I've mentioned before, I love elderflower and feel a strong connection to the elder tree (more on the “regal elder” and foraging here). Until recently however, the only things I've ever had made with elderflower have been using a sweet cordial. So when I saw a few recipes for elderflower fritters using the whole flower, I was immediately intrigued and wanted to attempt a savory version. The batter contains lemon zest and chives, because I felt that these would add some zest and complexity without overpowering the floral qualities. I served it with ponzu for a dipping sauce, but honestly, we didn't use it much as the fritters stand best on their own! The below recipe makes about 40-45 small fritters, enough for 4-6.

~10 medium-large elderflower heads, broken up into 40-45 small florets

1 cup all-purpose flour

Pinch yeast (champagne or baker's, I used champagne because I had some leftover)

6-8 fluid ounces apple cider or sparkling water

1/2 tablespoon finely grated lemon zest

1/4 teaspoon sea salt, divided

2 tablespoons diced chives, divided

Grapeseed oil, for frying

Ponzu or aioli for dipping (completely optional)

Shake blossoms to remove hitchhiking bugs and dunk into a large bowl of cold water. Remove from water, shake to remove as much water as possible (and probably more bugs!), and pluck smaller clusters (about 1-inch each) from larger clusters, removing as much large stem as possible (there will be some stems still, as that's how the flower clusters stay together). Set aside on a paper towel to dry more.

Whisk flour with yeast, 6 ounces cider, lemon zest, and 1/8 teaspoon salt until combined. Batter should be runny like pancake batter and will start to fluff up from the yeast. If batter is not runny enough, add some more cider then gently whisk in 1-1/2 tablespoon chives.

Pour enough grapeseed oil into a frying pan so that oil is 1/2-inch up the sides of the pan and heat to high.

Once oil is hot, dip florets (one at a time) into batter, shake off any large clumps, and fry in oil until golden brown, about 1-2 minutes on the side opposite the stem, then flip and fry another 30 seconds on the stem side.

Remove fritters and place on paper towel, then repeat with florets in batches until all are fried.

Top fritters with dusting of remaining salt and remaining chives. Serve with ponzu or aioli if desired.

Ponzu not needed, but a cocktail is!

Asparagus-Wild Onion-Umami

Asparagus-Wild Onion-Umami

One of my favorite spoils of spring are the wild onions. In the Bay Area, the Allium triquetrum or "three-cornered leek" is the wild onion that abounds and it also happens to be as lovely in flavor as it is in appearance. This wild onion is nicknamed "three-cornered" because of the shape of its stems and has the characteristic allium smell and taste with a delicate sweet note, especially when using its small, white, star-shaped flowers.

There are many ways to enjoy these "three-cornered leeks", but pairing them with asparagus deliciously highlights the season. In California, not many foods are truly seasonal so when they are I like to indulge. Browning the asparagus and chopped onion stems in butter with umeboshi brings in umami elements then topping with the sweet wild flowers and crunchy bits of sesame really knocks it out of the park. We made umeboshi last year with local wild plums, but store bought umeboshi or even miso can be used as a substitute if you do not have access to umeboshi - either ingredient will contribute the umami flavor that you're looking for. Recipe is adaptable to the amount of asparagus you have preference for strength of flavors. The below recipe will serve 2-4 people (in our house, definitely only 2!)

1 pound of asparagus (about 16 spears), tough fibrous stems removed

7 wild onion, aka three-cornered leek, stalks with flowers (there will be several flowers on each stalk)

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

3 umeboshi, finely chopped, or 1 tablespoon red or brown miso

1 tablespoon sesame seeds

For larger asparagus spears: Using a vegetable peeler, peel bottom of spear about 1-inch up from bottom and slice larger asparagus spears in half lengthwise. If you have thin asparagus spears, both of these steps can be skipped.

Remove wild onion flowers and dice stalks. Set aside.

In a cast iron pan, sauté butter over medium-high heat. Add asparagus, toss to coat, and cook until beginning to soften, about 1 minute. Add umeboshi (or miso in small pieces) and diced wild onion stalks, toss to coat, and cook until asparagus browns, about 3-5 minutes, tossing halfway through. Test an asparagus spear to see if it is flavored to your liking - if not, add more butter/umeboshi or miso/onion.

Remove from heat and top with sesame seeds and wild onion flowers. Serve hot.

Wild onion basking in the sun.

Bay Nut Mole Negro

Foraged bay nuts give the chocolate-coffee flavor you're looking for in a mole.

Most mole recipes leave me feeling overwhelmed and in a too-many-ingredients comatose. This one, although it does take about 2 hours to prepare, it a lot more approachable and some of that time is inactive, which means you can spend it on your other side dishes. Yes, this recipe is likely not as complex as others you may find, but even just with two chiles and some other key ingredients, you can create a delicious and robust mole negro.

“As bay nuts do not contain sugar or cinnamon, I added a little of each. If you don’t have bay nuts, replace them with mexican chocolate (such as Ibarra) and skip the brown sugar and cinnamon. ”

Also unique to this mole is that instead of the traditional chocolate, I chose to use bay nuts. Bay nuts are a foraged find from the bay laurel tree (more on bay nuts and foraging here). The bay nut is a member of the avocado family that, when roasted, becomes akin to a combination of chocolate and coffee - ideal for mole. Recipe serves 6.

2.5 pounds skinless chicken thighs and/or legs

~1-2 teaspoons salt

2 tablespoons grapeseed (or other neutral flavored oil), divided

1.5 cups low sodium chicken broth

Juice and zest from 2 blood oranges

2 cinnamon sticks

1 yellow onion, chopped

1/4 cup almonds, chopped

3 large garlic cloves, diced

2 teaspoons cumin seeds

2 teaspoons coriander seeds

1.5 ounces dried pasilla chiles, stemmed, seeded, and torn into strips

0.5 ounces dried negro chiles, stemmed, seeded, torn into strips

3 prunes, chopped

1 teaspoon dried oregano

2 ounces roasted bay nuts, chopped (mexican chocolate can be substituted for bay nuts, brown sugar, and cinnamon)

1 tablespoon brown sugar

Chopped fresh cilantro, queso fresco, avocado, and corn tortillas (to serve)

Rub chicken all over with salt. Heat 1 tablespoon oil in large pot (I use my large Le Creuset pot) over medium-high heat. Brown chicken on both sides, about 3 minutes per side.

Add broth, blood orange juice, and cinnamon sticks then bring to a boil. Reduce heat to medium-low; cover and simmer until chicken is tender and just cooked through, about 25 minutes.

Meanwhile, heat remaining 1 tablespoon oil in large saucepan over medium heat. Add onions and garlic and sauté until softened and beginning to caramelize, about 10-12 minutes, stirring occasionally. Add almonds, cumin, coriander, and chiles. Reduce heat to medium-low and cook while stirring until chiles soften, about 4 minutes.

Using tongs, transfer chicken from pot to large bowl. Pour chicken cooking liquid into saucepan with onion-chile mixture (reserve pot). Add blood orange zest, prunes, oregano, bay nuts, and brown sugar to saucepan. Cover and simmer until chiles are very soft, stirring occasionally, about 30 minutes. Remove cinnamon sticks and discard.

Transfer sauce mixture to food processor or blender and purée until smooth; return to reserved pot. Season sauce to taste with salt. Coarsely shred chicken and return to sauce; stir to coat and re-heat chicken.

Serve topped with cilantro springs, avocado, corn tortillas, and queso fresco (if desired).

Pair with: Vinegary red cabbage slaw (the vinegar is a great contrast to the dark, rich mole), roasted delicata or butternut squash.

Toasted Dock Seeds

Raw dock seeds are beautiful, but (in my opinion) not as tasty.

Dock, or Rumex spp. (general and foraging info here), has tart edible leaves that are available in the spring, but the real treat to me are the seeds of the dock, which you can find in the later spring through summer on the West Coast (and most of the world). The seeds can be eaten raw, but are better toasted and, being a member of the buckwheat family, can be used like you would buckwheat (which is a seed itself, not a grain). Try mixing the seeds into a granola or dough for crackers, sprinkling them over poached fish, or grinding them into a flour and using it for baking.

To remove the seeds from the plant, first wash and shake out the dock to dry it then simply run your fingers down the length of the stalk, pulling off seeds as you go. You might want to do this outside, as dock seeds have a tendency to "jump".

Toast the seeds in a cast iron pan on medium high, stirring frequently to cook the seeds evenly. In my experience, 1 cup of seeds in a medium cast iron pan will take about 10 minutes, but this will changed depending on how many seeds you're toasting at once and size of pan (less seeds = more exposure to heat).

Dock seeds, toasty brown.

Cornmeal-battered nopales with smoked paprika

I had a very, very productive nopal cactus in front of my house in Oakland. So productive, in fact, that harvesting and processing its fruit felt like a part time job in the summer/fall. Nopal is the common name for members of a group (the Opuntia genus) within the cactus family, with the plural being nopales. Usually however, I see nopales referring to the cactus pads specifically, with prickly being the fruit. If you see a big cactus with large flat "paddle" leaves with thorns and bright red fruit, it's an Opuntia cactus and is edible. Some are better tasting than others and there are also better times to harvest the cactus pads. See my past post on harvesting nopal cactus pads for more details. The best piece of advice is to be careful because the thorns on the fruit have a tendency to jump onto you!

Oh how I loved my very productive Opuntia cactus.

This recipe is really just guidance, as the specific quantities aren't incredibly important. If serving as an appetizer or in tacos, which are probably the best uses, make about 1 medium cactus pad per person.

Nopales (cactus pads) that are at optimal tenderness - just remember to remove the spines!

What I like about it is the dry heat method of pan-frying helps to limit the viscous quality that can happen with nopales (similar to okra). And, of course, cornmeal crunch is always appreciated. Feel free to play around with the cornmeal to flour ratio, herbs and spices, and dipping sauces. I have also thought about cutting the nopales into strips before battering and frying, which might help further reduce the viscous qualities and make for easier serving. Enjoy!

Young/tender nopales pads

1 part medium-grind cornmeal (about 1/2 cup for 4 medium cactus pads)

2 parts all-purpose flour (about 1 cup for 4 medium cactus pads)

Smoked paprika or chili powder (about 1 teaspoon for 4 medium cactus pads)

White or black pepper (about 1/4 teaspoon for 4 medium cactus pads)

Salt (about 1 /4 teaspoon for 4 medium cactus pads)

Eggs, beaten (1-2 eggs for 4 medium cactus pads)

Oil for frying (about 1/3 cup for 4 medium cactus pads)

Cactus pad with spines removed.

To prepare

Coating with all-purpose flour before the egg and cornmeal batter.

Remove thorns from cactus pads (see this post for information on removing spines). Set up a plate with paper towels to lay the nopales after you fry them.

Mix cornmeal, 1/2 cup flour, spices, and salt on a plate. Set other 1/2 cup all-purpose flour on a different plate.

Toss each cactus pad in pure flour mixture to lightly coat then dip in beaten egg and shake off excess. Dredge each egg-covered pad in the cornmeal mixture so that it covers all sides and set aside.

Add oil to frying pan - oil should be about 1/4-inch high - and heat on high.

When oil is hot, cook nopales about 2 minutes per side, or until browned, and set on paper towel. You may cook these in batches if needed, adding more oil as necessary.

Serve hot with a squeeze of lemon and a dipping sauce such as aioli, romesco, or an herb blend (optional). Cactus can be cut into strips prior to serving.

Frying to a golden-brown.

Bay Nut Ricotta Cake

A lovely use of foraged and roasted bay nuts

Cake in foreground, my brother’s art in background.

Here’s the deal: everyone likes coffee and chocolate. Okay, so that may not be entirely true, but who are we kidding? I probably don’t want to associate with those individuals anyway.

For those of us with *good* taste, the knowledge that there is a wild edible commonly found on the West Coast (the bay nut - more including foraging info here) that, when roasted, produces a flavor that can be likened to a combination of coffee and (bitter) chocolate is mind blowing. Now think about taking that amazing ingredient and adding it to a ricotta cheesecake - not bad. This brings us to the bay nut ricotta cake (which is really more of a tart, but using cake since a ricotta cake might be more familiar to some…)

“A graham cracker crust also works, but doesn’t have the same rustic qualities as buckwheat flour. Buckwheat is also gluten free - make the dessert gluten free by replacing the all purpose flour with a gluten free substitute. An entirely buckwheat crust can work, but is a little too crumbly. ”

Crust Ingredients

3 tablespoons ground bay nuts (medium grind, as you would for french press coffee). You can use a coffee or spice grinder or chop with a knife.

1 cup buckwheat or other flour of choice (can use all -purpose, but crust won’t be as dark)

2 tablespoons all purpose flour (to help bind - if you want the cake to be gluten free, use another gluten free flour mix)

1/3 cup granulated sugar

1/4 teaspoon salt

7 tablespoons unsalted butter

1-2 tablespoons cold milk or water

Filling Ingredients

16 ounces ricotta cheese

1/3 cup granulated sugar

1/4 cup roasted bay nuts, ground (medium grind, as you would for french press coffee). You can use a coffee or spice grinder or chop with a knife. Coarsely ground also works for more definition/larger chunks.

1 egg, lightly beaten

2 teaspoons juice from an orange (optional)

1 teaspoon orange zest (optional)

Topping Ingredients

8 oz. sour cream

3 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Preheat oven to 350 degrees F and grease a springform pan.

For crust: Mix 3 tablespoons bay nuts, flours, 1/3 cup sugar, and salt. Cut in butter with pastry blender, fork, or fingers and mix until pea-sized crumbs. Add water or milk until dough comes together when pressed, but is not too wet. Press into greased 9” springform pan and bake for 12-15 minutes until firm and lightly browned on edges. Remove from oven and cool completely.

For filling: Whisk filling ingredients until thoroughly mixed. Pour onto cooled shell, bake in oven for about 35-50 minutes, until cake is set and jiggles only slightly. You make need to cover with foil if the crust edges become too brown.

For topping/final step: Remove from oven and let stand for 15-20 minutes while you mix together the topping ingredients. Spread out topping mixture and put back in the oven for another 10 minutes. Remove and cool until served.

Crust me! I like to smash the crust up higher than the filling will be for a more dramatic rustic look.

Fried Mussels with Wild Greens

Armageddon shmarmageddon - I've got my mussels.

The primary ingredients to this dish are foraged (Baker Beach for mussels and Temescal for greens), so as long as I can rustle up the other ingredients and a burner, I’ll be sitting pretty post-apocalypse. The wild mussels were foragedand thus, quite “rustic” making it virtually impossible to clean them thoroughly and necessitating cooking and taking them out of the shell before consuming, so I decided to fry them. The below recipe serves 3-4 as an appetizer.

1 pound fresh mussels, rinsed and scrubbed as best you can

1 cup cornmeal, medium grind

1/2 teaspoon paprika

1 egg, beaten

1/2 teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons high heat oil, such as grapeseed or coconut

1 lemon wedge (can use a slice from dressing, below)

Foraged greens, such as dandelion and sow thistle tossed with lemon-olive oil dressing (Combination of juice from 1/2 lemon, 1 tablespoon olive oil, and 1/2 teaspoon of mustard for 1 cup greens) - I like a lot of greens, but whatever is best for your preference of fried mussel:green ratio

Boil mussels in a large pot of water (rolling boil) for about 7 minutes, or until mussels open. remove mussels from shell, drain any excess water, and set aside. Discard any mussels that do not open.

Meanwhile, mix cornmeal with paprika and salt on a plate. Dip mussels in beaten egg a few at a time, then toss in cornmeal mixture to coat.

Heat oil on medium-high. Once oil is hot, add mussels and brown on each side, about 3-5 minutes total. Remove from oil, place atop wild greens tossed with dressing, drizzle with squeeze of lemon, and sprinkle with paprika.

Serve with aioli, if desired.

Bay Nuts

The cacao-coffee bean of foraged finds.

Here’s the deal: everyone likes coffee and chocolate. Okay, so that may not be entirely true, but who are we kidding? I probably don’t want to associate with those individuals anyway.

For those of us with *good* taste, the knowledge that there is a local edible easily foraged that, when roasted, produces a flavor that can be likened to a combination of coffee and (bitter) chocolate is mind blowing.

Where to find them: From the West Coast/California bay laurel tree, Umbellularia californica. This may sound obvious, but the bay tree does not always have nuts - the nuts appear from October - December, or even as early as September in Central California or when it's an especially hot year. Also, some years are better than others and some produce only a small amount of nuts - just because you don't find nuts on a tree one year doesn't mean they won't be there the next!

The bay tree leaves can (and should? why buy?) be used as you would use bay leaves purchased from the grocery store, but are very strong, with a ratio of 3:1 (tree bay leaf: store bought bay leaf).

The nut itself is a close relative of the avocado (Lauraceae family) and it looks like an avocado pit with a thin layer of flesh. The flesh goes from a bright green (unripe) to purple (ripe) and is technically edible, but rots very quickly. You'll know it's rotten when the outside is a goopy, gross, mess “this-will-make-you-sick” texture. The real treat is when you roast the nut itself on the inside of the flesh. Before roasting, or if not roasted properly, the nut is extremely bitter and astringent, similar to acorns and olives before they are cured. You will NOT want to eat the nut before roasting.

To roast the nut:

Peel off that goopy exterior. Sometimes you can find the nuts by their lonesome, in which case, score! Less to do. Sometimes, you peel them and they look fine. Othertimes, you peel them and they look gross/moldy - throw these ones out.

Wash the nuts - remove any excess goop.

Dry the nuts. I have seen directions indicating that the nuts need to be dried then stored for 1-2 years, but I don't have the patience for that and in my experience it just takes a few weeks in the dry climate of the Bay Area to remove the moisture. To dry, lay them out to open air until the water evaporates then store in paper bags or other breathable containers (an open bowl or jar) in the dark.

Roast the nuts on a baking sheet in a single layer at 350 degrees F. This usually takes about 1 to 1.5 hours, but you’ll know they’re done when the insides look brown/black (some will crack open to reveal this). Some recipes call for 450 degrees F for 45 minutes - I previously said that either way works, but have heard that 450 makes them too toasty too fast. Up to you, but I would check them every 20 minutes or so.

Crack open the shells with a nut cracker (teeth also work, but everyone cringes when I do that) and eat the nuts as you choose. They have a slightly bitter taste, but for those that like super dark chocolate, it’s delicious. Note that bay nuts possess a mildly stimulating effect, similar to caffeine.

Suggested uses (so far, I’m still experimenting):

One their own (haven’t made them covered in chocolate yet, but I’m sure this would be decadent and plan to do so). Pairing with whiskey is awesome.

Bay nut mole - substitute chocolate for bay nuts. Don’t look back.

Bay nut ricotta cheesecake - I have done this twice now and the recipe is lovely.

Bay nut brittle

Bay nut hot cocoa?

Bay nut chocolate bars - working with the Culinary Institute to make this happen, but I know that Madre Chocolate has done it in the past!

Exploring Elderberry

Bright, bittersweet, alluring berry taste for a variety of uses.

Note: The below is also published in the Fall 2016 edition of Edible East Bay.

Harvesting elderberries.

The culinary and medical applications of both elderflowers and berries are many, which has led to the plant’s frequent appearance in world mythologies. Among pagan traditions, the elder tree is attributed with powers from protection and healing to vivid dreams and removal of negative spells. It is fun to use both harvests from the tree (flowers and berries) in a dish, such as elder almond pound cake. See previous post, the Regal Elderflower or Exploring Elderberry for more information about processing elderflower and the plant's uses in general.

Autumn’s elderberries—the dark and pungent counterpart to the sweetly fragrant blossoms—offer flavor that varies from tree to tree. At its best, the berry is juicy and bittersweet, similar to a blueberry, but smaller and more acerbic. At its worst, the bitter flavor shines through and the texture can be coarse and dry.

Processing the berries by cooking or drying will render them safe and improve the flavor. Elderberries are often cooked down into a cordial syrup, made into elderberry jam or wine, baked into pies and cakes, or dried and used as you would use dried currants. Dried berries can also be rehydrated by simmering with water and sugar for a more “stewed” flavor.

On Foraging: The elder plant found in Northern California (and most of the Western United States) is Sambucus cerulea, also known as blue elder for it's dark-blue berries. This shrub, which can grow to 30 feet high, has reddish bark and pinnate leaves that grow opposite each other. Like elder plants everywhere, it prefers warm, damp environments, so look near flowing water inland from the foggy coast. If you noted where you found elderflowers in early summer—you can return now through September (in our region) for the berries.

Some examples of using elderberries: Elderberry cordial, jam, elderberry buckwheat tart.

Dark blue elderberries with whitish bloom.

Prickly Pear Harvest and Processing

A few easier ways to take on the prickliest of pears.

By now one would think I should be a master prickly pear parer, but alas - I still acquire many little spikes in my hands and in other peculiar places (for example, I once found a few on my tongue over a week after processing) when I pick and process the fruit, just less than before.

The cactus plant in front of my cottage is such a large and active producer of prickly pear fruit (also known to Spanish-speakers as "tuna") that I’ve found during the late summer and fall, prickly pear harvesting and processing can be a part-time job. Luckily, I have some skills from my time in Arizona and have a few fine-tuned processes allowing for maximum production in minimal time with as few pricklies in fingers as possible.

Process 1: If you want to keep the whole fruit intact for smoothies and other recipes requiring the flesh. Note that this process is more difficult, but uses as much of the fruit as possible, preserving fiber and other beneficial nutrients found in the flesh. However, when you use the whole fruit there are black seeds that are very hard and difficult to remove or pulverize. I don't mind these seeds, but I've found that others do.

Step 1. Pluck the pears using tongs -in fact, use tongs throughout this whole operation wherever possible. Be very careful which way the wind is blowing - obviously, try to avoid standing downwind and close your eyes if you see danger.

Step 2. Set up your operation - place pears in a big bowl and get ready to peel them. I like to have 3 bowls for this - 1 for the unpeeled pairs, one “working bowl” where you slice them, and one for peels.

Step 3. Cut off each end of the pear.

Step 4. Make a slice down the middle and scoop out the fruit. This is a pretty cool step because the fruit comes away from the skin quite naturally. Toss skin in one bowl and fruit in another. This loses some of the fruit on the edge of the skin, but there’s really no other way unless you want to get stickers everywhere.

Step 5. Consume or freeze for later use.

Process 2: If you just want to use the juice. Note that it is not incredibly efficient and the flesh is discarded. However, I've started doing this process more often than not because of how productive my cactus plant is and for the following benefits: This process is way easier, less time consuming, and you'll have fewer spines (if any) in your hands at the end of it.

Step 1: Pluck the pears using tongs and put them into large ziplock bags. Again, be very careful which way the wind is blowing - obviously, try to avoid standing downwind and close your eyes if you see danger.

Step 2: Freeze the fruit overnight or for up to 1 year.

Step 3: Pour frozen fruit from bag into a colander and rinse. Place colander over a large pot or bowl and put something heavy on top of the fruit (I use a very large mason jar filled with water).

Step 4: Wait for 1-2 days (depends on temperature) as the juices come out of fruit, through the colander and into the bowl. You can press down on the heavy object and slice open the fruit as needed to encourage this process.

Step 5: Once as much juice is out of the fruit as possible, strain juice through a fine mesh colander or cheesecloth (to remove any remaining spines) and discard pulp.

Step 6: Use juice immediately, refrigerate for up to a month, or freeze for up to a year.

Prickly pear granita: Blend frozen pears with ice and lime. Add black pepper or cayenne for an optional spicky kick.

Prickly pear recipe suggestions: Prickly pear margarita, prickly pear manhattan, prickly pear granita, prickly pear cheesecake, prickly pear chutney/jam, prickly pear sorbet.

Nasturtium: So much more than a (pervasive) flower

Nasturtium mezcal margaritas: An impromptu preparation for an outdoor happy hour.

Nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus) grows everywhere - everywhere - in the Bay Area as well as many other parts of the country. It flourishes in parks, gardens, and along sidewalks pretty much year-round, except when it gets very cold or very dry. The plant is sprawling and iconic - even if you do not immediately know what I am talking about, you have probably seen nasturtium many times or perhaps tasted the flowers in a salad mix from the farmers' market or restaurant. The flowers are bright orange, yellow, or sometimes red with five petals on a single stem and leaves that look similar to lily pads, but thinner. The plant comes by way of South America and my guess is that it was transported here because it is so visually appealing, grows easily, and has a tasty, unique flavor.

What I love about the nasturtium plant is that with its mustard/radish/wasabi-like flavor and cheerfully spunky appearance, it is very approachable for even the biggest wild food skeptic (as long as said skeptic doesn't have an aversion to pungency). However, when you dig a little deeper, there are so many more possibilities than just using the fresh flower as a garnish or in salads. The leaves have a slightly thick, viscous quality to them, similar to okra, but I the sharp flavor cuts this a bit and the viscosity is helpful when you want to thicken a dish, such as a risotto or stew.

Freshly picked nasturtium seed pods

Sweet pea flowers in foreground, baby nasturtium leaves in background wrapping shrimp (wish I got a better photo of the nasturtium!), rhubarb broth.

My first close and consistent experience with nasturtium was when I worked in a restaurant that used the flower to garnish mezza platters (hummus, tapenade, etc.). Being me, I would often grab a bunch of the leftover stems and take a big bite for a peppery "jolt" to keep me going throughout the night. On the other (more calculated) end of the spectrum, in the past few years I have been using the flowers in cocktails and experimenting with the leaves (either fresh in a salad or lightly cooked) and seed pods (pickling them is amazing - check out this recipe for California capers) Baby nasturtium flowers even made their way to the Noma menu when I had the opportunity to eat there and nasturtium pesto is a regular staple on the ForageSF Wild Kitchen dinners, or at least it was the few times I helped out.